In Greek mythology, Medusa was one of three so-called “Gorgons” and the most beautiful of the sisters. She served in the temple of Athena, the goddess of wisdom. One day, Poseidon—the god of the sea, and an archenemy of Athena—slept with Medusa in the goddess’ temple, the Parthenon (literally: “virgin’s chamber”). Enraged by this desecration of her sanctuary, Athena transformed the Gorgon Medusa into a terrifying creature with large fangs, snake hair, a squashed nose, oversized eyes, and a long, protruding tongue. In a later episode, the Greek hero Perseus cuts off Medusa’s head and hands it to his protector, the goddess Athena. She then pins the head to her breastplate, the “aegis”—a goatskin armour that she had received from her father, Zeus, at her birth.

Medusa’s gaze turned anyone who looked at her face to stone. For this reason, Greek artists created so-called “Gorgoneia”, depictions of the head of the Gorgon Medusa. These were said to have a deterrent and protective function. Early depictions from the 7th and 6th centuries BC show her as a terrifying monster. However, in the following centuries, artists returned to depicting her former beauty, and many images once again showed her beautiful features, although the menacing snakes in her hair remained a defining characteristic.

Such a Gorgoneion can be admired in a Greek tomb complex dating from the 4th century BC. Located in the Sanità district in the heart of Naples, the complex is known today as the “Ipogeo dei Cristallini”. The tombs can be accessed via a rear courtyard, with numerous steps leading down to the ancient street level. In 1889, Baron Giovanni di Donato discovered the four ancient burial chambers carved into the rock while digging a well in the courtyard of his palace. Tomb C is particularly fascinating because its colourful decorations are in unusually good and surprisingly fresh condition.

The main chamber of Tomb C is modelled on an ancient banquet hall. Eight klinai (dining couches) with cushions—which obviously served as burial places for several centuries—stand against the walls. Above them are the names of the deceased in large letters. Garlands adorn the walls, a bronze candelabra stands at the entrance, and a metal ceremonial bowl hangs on the wall opposite—all of which are painted, of course. With shaded areas, highlights and details finely carved into the plaster and paint, the illusionistic painting here was created with great finesse. Even the terrazzo floor with mosaic inlay is, in reality, a painted illusion.

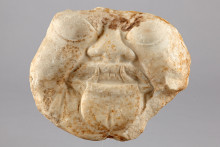

In the lunette of the central wall is a large, three-dimensional Gorgoneion carved from tuff. It is positioned in the centre of a painted aegis lined with tongued snakes. For centuries, a ventilation slot above the door probably offered a view into the closed burial chamber—directly into the eyes of the Gorgon Medusa.

Polychromy Research

Learn more about polychromy research at the Liebieghaus here.

At the end of 2023, the Liebieghaus Polychromy Research Project team was invited by the Neapolitan Martuscelli family, descendants of Baron di Donato, and the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio per il comune di Napoli to examine the preserved colours and the technique used to apply them in Tomb C. The burial chamber was studied in depth over the course of several days. The Martuscelli family had already commissioned various Italian institutions, such as the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro in Rome, to conduct scientific investigations of the colour materials, which our team was able to supplement.

We were particularly interested in the colours of the Medusa. Heinrich Piening, a restorer and scientist who has been a member of our research team for twenty years, identified the pigments used with the help of UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy (FORS). This non-contact, non-destructive scientific investigation method involves measuring the absorption of light by coloured surfaces and is equally suitable for mineral pigments and organic dyes. Additional information was provided by photographic methods using UV and infrared light, enabling organic pigments and Egyptian blue to be reliably identified on site.

The painterly execution of the colouring of Medusa’s head was documented with several hundred photographs. Evaluation of the UV-Vis measurements revealed that, in addition to Egyptian blue, cinnabar and madder lake, especially yellow, red and brown iron oxides, such as hematite, were also used to colour Medusa’s face. Thanks to its exceptional state of preservation, the painting provides an impressive testimony to the revolutionary development of illusionistic Greek painting, which reached its first peak at the end of the 4th century BC. The painted aegis with its numerous small snakes is a wonderful example of this virtuoso use of light and shadow, creating an illusion of space and forming a harmonious unity with Medusa’s sculpted face.

An experimental reconstruction was used to visualize the original appearance of the Gorgon Medusa. A digital 3D model of Medusa’s head was created using photogrammetric surveying of the Gorgoneion and was then 3D printed in quartz sand at a scale of 1:1. The dark, porous quartz sand has similar properties to the volcanic tuff of the original. Unlike marble, which is an ideal surface for painting, this dark, porous stone requires a primer before paint can be applied.

Our investigations revealed that the paint was applied using a combination of fresco (milk of lime) and secco (tempera) techniques. First, an extremely fine primer, around 1–2 millimetres thick, was applied using active, aggressive lime putty. When working with the fresco technique, it is important to avoid complete drying, since the lime only retains its binding power when moist. Once the lime has set, an extremely durable paint layer is formed.

This milk of lime painting technique is only suitable for the first rough application of paint. The modelling of the skin, as well as the fine details of the eyes, eyelashes and eyebrows, was then carried out using an organic binder—in our case, most likely egg—in a tempera or secco technique.

The fresco painting process must be carried out quickly. In the case of the reconstruction presented here, it was completed within a few days. By contrast, the necessary preparations were extremely time-consuming. Numerous tests were carried out to determine the correct ratios for mixing the lime and pigments, since the final colour tone only becomes apparent once the paint is completely dry and can only then be compared with the original. Furthermore, painting with milk of lime requires experience and precision, as each brushstroke must be executed perfectly the first time and match the original as closely as possible.

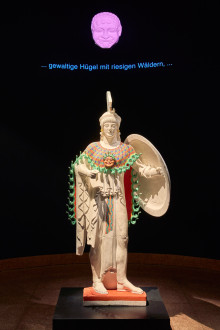

For the final painting in secco (tempera) technique, however, more time could be taken. The painting process was carried out by the archaeologist Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann in an open workshop and completed in October 2024. The new reconstruction was part of a project presentation entitled “Medusa’s Colors: A ‘Gods in Color’ Project” in the galleries of the Liebieghaus’ antiquities department.

The colour reconstruction is currently on display as part of the special exhibition „Isa Genzken Meets Liebieghaus“ and will remain there until 26 October 2025. It is displayed opposite a work the contemporary artist Isa Genzken entitled “Airplane Window (Medusa)” from 2011: The interior panelling of an airplane wall with two window openings is covered with a photograph of the Mona Lisa on the left and a portrait of the artist herself on the right, both looking upwards. Superimposed on these images is the motif of the famous Medusa shield by the Baroque artist Caravaggio.